Sceptic at Large

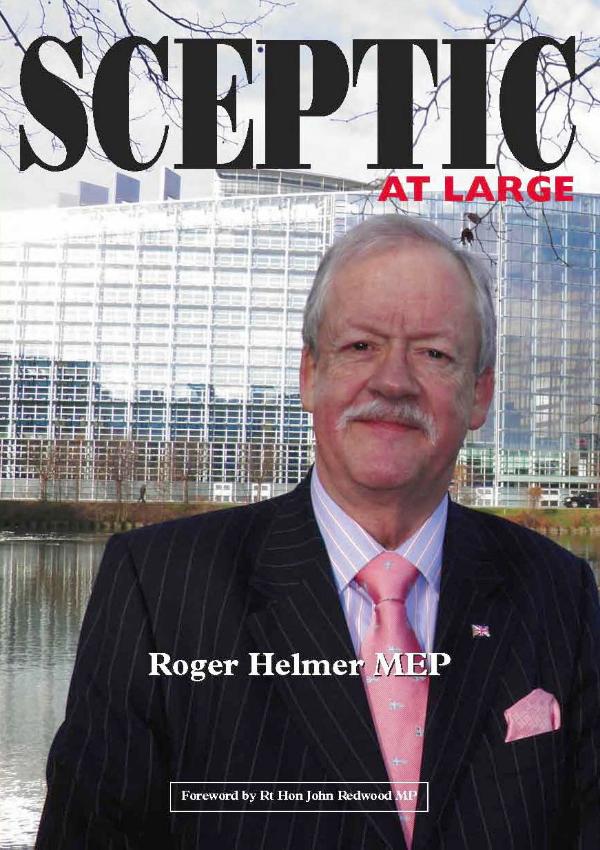

Author: Roger Helmer MEP

"Well informed and merciless” - Lord Lawson

“Roger Helmer revels in controversy” - Rt Hon. John Redwood MP.

A controversial critique of the European Union by maverick Conservative MEP Roger Helmer.

In this highly readable book, one of the Conservative Party’s most colourful and controversial figures gives his views on where the EU is going wrong and why David Cameron’s policies are contributing to the unfolding disaster in Brussels.

Covering a wide range of policy topics, Roger Helmer explains how democracy is being eroded robbing freeborn Englishmen of their birthrights of freedoms and democracy that have taken generations to secure. Roger also casts a sceptical eye over the Climate Change industry, the grip of political correctness on the EU and how the rural way of life is being undermined by an increasingly urban chattering class.

The book closes as Roger peers into the future to predict what the next five years has in store for Britain, the EU and for the British people that he is so proud to represent.

Illustrated with photos, this book combines serious political thought with an entertaining writing style that has made Roger Helmer one of the more popular bloggers on the centre right of the political spectrum.

About the Author

Roger Helmer MEP?was first elected to the European Parliament in 1999 for the East Midlands of England region. In 2006 he was expelled from the Conservative Group, and later readmitted after public pressure. He has been re-elected top of the poll at every election since. Roger formerly worked for Procter & Gamble and with Coats Viyella in Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia and Korea.

Extract

copyright Roger Helmer

Chapter 9

Peering into the Future

Where is the EU going?

“Forecasting is difficult, especially about the future”. This wonderful line has been attributed to many sources, not least Yogi Berra, Dan Quayle and Victor Borge. Or I suppose it could have been Woody Allen (I love his line “I’m not afraid of dying -- I just don’t wanna be there when it happens”).

Forecasting is indeed difficult. I love to read the predictions of economic journalists (and to hear the Today Programme’s racing tips), but of course if they had a better-than-average success rate, they’d be coining-in money on the stock exchange (or at the races), not offering their tips to the credulous.

So I start with a caution that applies to all predictions. Nonetheless, I think it’s worth drawing out some useful trends that suggest where the EU might be going in the future.

A shrinking economy

There are a number of long-term projections from highly respected institutions which forecast that in terms of share of the world economy, emerging Asia will increase over the medium term, the USA will roughly hold share – and the EU will decline.

A 2005 report from the UK Treasury showed the US share of global output holding steady at around 20% between 1980 and 2015. China and India together increased from 6% to a stunning 27% -- while the EU declined from 26% to 17%. Goldman Sachs are forecasting that by 2050, China will have 28% of world GDP, the USA 13%, India 12% and Euroland a paltry 8%, barely half its current share of global GDP.

There are two major factors driving GDP and share of world trade, and they are firstly population, and secondly productivity. In the case of population, we can make rather reliable predictions, because demographic changes move slowly and are predicated in large part on existing birth-rate trends.

China faces demographic problems, partly as a result of the one-child policy, although that is being relaxed. But China’s problem is a couple of decades behind Europe, where catastrophically low birth-rates are well below replace-ment levels in many countries -- even

in those Catholic countries that traditionally had higher birth-rates. So a large part of the EU’s decline is already set in place.

America on the other hand is a much younger country with a high level of (predominantly young) immigration, so it will not face the same demographic problems.

Then there is the question of productivity. Europe has had a stubborn problem of productivity, and has generally been unable to match progress seen in the US. China as a rapidly developing nation has much more headroom to increase productivity with new investment.

So the EU starts in a bad place, but (as you will have seen in the earlier parts of this book) it also seems to have a regulatory death-wish. It insists on piling ever more regulation on industry, reducing efficiency and adding to unit labour costs with ever harsher administrative requirements. The Working Time Directive, the Agency Workers Directive, parental leave, health and safety, REACH (the chemicals directive), each adds hugely to the costs of doing business in the EU. Plus of course carbon taxes, emissions trading and a cat’s cradle of regulatory burdens designed to “mitigate climate change”. These measures add billions to industry’s costs, and devastate competitiveness.

Many of these measures seem perversely designed to drive business and jobs and investment out of the EU altogether – and ironically, to drive it to foreign jurisdictions with (frequently) lower environmental standards. So we lose the business, and potentially increase the pollution at the same time.

Recent reports suggest that there is massive environmental pollution taking place in China as part of the rare earth extraction necessary for (inter alia) building Chris Huhne’s wind turbines, and electric cars. And of course most of Huhne’s “Green Jobs” – where they happen at all – will happen in China.

There was the Tobacco Directive, which moved the production of higher strength cigarettes out of Nottingham (Imperial Tobacco) and offshore to Bangladesh or Brazil.

There was the battery hen regulation that moved a huge swathe of egg production from the EU to the Ukraine, India, Thailand and Taiwan – so EU farmers lost out, and (on balance) so did the chickens.

There are new anti-discrimination proposals on pensions and financial services that could lead to EU consumers buying insurance off-shore.

There are the environmental constraints on ship-breaking which have led to ships being broken up on beaches in India where the work-force includes children in flip-flops – with no safety equipment at all.

But the biggest problem is the plethora of measures designed to curb CO2 emissions. These have made the EU a terrible place for energy-intensive industries like glass and ceramics, metals, cement, and paper.

The democratic deficit

My colleague Dan Hannan MEP has a catch-phrase that I have shamelessly plundered and quoted: “The EU is making us poorer, and less democratic, and less free”. In the first part of this chapter I have sketched the reasons why the EU is making us poorer. I mean, of course, poorer than we would otherwise be – not poorer than we were twenty years ago.

Apologists for the EU project like to quote large increases over the years in standards of living in the EU, and increases in trade. They cheerfully ignore the fact that the rest of the world (broadly speaking) has done as well or better. The test is not whether prosperity has grown in the EU, but whether the policies and institutions of the EU have given Europe any advantage compared to the rest of the world. The answer is clearly “No”. We have seen how the EU is declining in terms of share of world trade.

But less democratic? How can I, as an elected MEP, say that? Surely democracy is all about voting, and EU citizens get the right to vote? But there are fundamental reasons why the EU is not, and cannot be, democratic. For a start, almost nobody ever gets to be an MEP unless they have at some stage gone to a Party meeting and indicated an interest in becoming a candidate. And what sort of people might do that? Overwhelmingly, people who are enthusiasts for the European project.

There are of course some exceptions. I and one or two Conservatives stood for election because we were appalled at the way the EU, and Britain’s relationship with it, were developing. And candidates for rejectionist parties like UKIP are frankly and openly opposed to the EU project. But the great majority of MEPs are euro-enthusiasts.

There was an excellent illustration of this mis-match between elected MEPs and their constituents when we voted on a report welcoming the EU Constitution (later transmogrified into the Lisbon Treaty). The great majority of French and Dutch MEPs voted for the report. But in subsequent referenda in both countries, the people (God bless ’em) rejected the Constitution by a significant margin.

It seems that voters are starting to catch up with this mis-match. In the past, they simply voted red or blue or yellow in Euro-elections, just as they would in General Elections. But the rapid rise in the UKIP vote in euro-elections (they came second, ahead of Labour, in 2009) suggests that voters have realised that none of the major parties reflects their view on the EU, and have reacted accordingly.